Petronius on NHS Reform Proposals

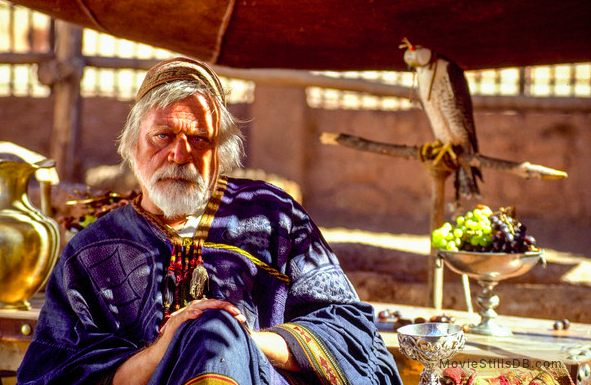

THE timing and likely effectiveness of Matt Hancock’s proposed re-organisation of the NHS during a pandemic immediately brought the famous quote of Petronius Arbiter to mind. He was a Roman official at the time of Nero and the observation most often attributed to him seems apposite, despite the lack of detail about future plans available at this moment.

“We trained hard—but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams we were reorganized. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing, and what a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while actually producing confusion, inefficiency, and demoralization.”

Leaked news of the proposed NHS legislative changes fly in the face of the most recent in-depth research by Henley Business School into existing governance and executive governance structures within the NHS (a “landmark study of NHS” according to the Health Service Journal) undertaken for my recently published The Independent Director in Society co-authored with Andrew Kakabadse and Filipe Morais.

WE found NO requests or any demand to (re) centralise executive powers back into the well-washed hands of the Secretary of State or the Department of Health to improve NHS performance and governance. We did find that 89.1% of NHS respondents highlighted a lack of resources (both people and finances) to cope with day-to-day pressures in the NHS. 0 (ZERO)% of our NHS respondents requested further intervention from either the Department of Health or the Secretary of State nor any need for them to “take back control” to help NHS governance and/or outcomes improve.

Interestingly co-author Professor Andrew Kakabadse also undertook the first comprehensive investigation of the Civil Service in 143 years (The Kakabadse Report, 2018). Amongst many other things, he found that ministerial (& also spad) churn along with ministerial ineptitude – primarily attention-seeking or well-intentioned low information but headline grabbing policy interventions – combined to represent a significant factor holding back both good government and the efficient achievement of agreed policies, manifesto commitments and targets.

Worse still, though State Department and/or Minister led policy interventions didn’t lack grand vision and ambition, they regularly suffered an extremely high failure rate or changes in ministerial portfolio. His report noted: “Ministers were identified as not necessarily knowledgeable in their area of office and at times unclear about the realities of policy delivery. Yet, despite this, they were also characterised as ‘ambitious’, ‘wanting to lead’, seeking to ‘initiate change’ and to ‘leave a positive legacy’.”